This week had a special coming-home feeling for me as I went back to the classroom for a Syntropic Agroforestry course. It was watching the Life in Syntropy short film on YouTube that got me started on a now eight-year, never-ending rabbit hole of agroforestry as an important tool on our food systems transformation journey. The teachings of Ernst Götsch and the opportunity to visit Fazenda Ouro Fino from Henrique Sousa in Brazil early in my journey made me a believer and investor in the potential of agroforestry as a key system in the future of agriculture. I can still vividly remember walking through Henrique’s mature 30-year-old agroforestry in awe, with its abundance and a whole new way of farming. Since then, I’ve visited lots of farms and dived into lots of theory—from scientific research to conferences—eventually becoming a speaker myself on everything related to agroforestry in impact investing conferences around the world.

My dirty secret until this weekend was that I had never grown my own food, and apart from the usual corporate team-building or ceremonial tree planting—where all you have to do is put the tree in the hole and smile for the cameras—my experience with actually planting a tree myself was close to non-existent. Worse still, planting a whole agroforestry system under the sun.

My rational mind found dozens of excuses not to sign up for the course. My mind’s favorite one was that I was too busy designing a new plan for an 1,800-hectare farm with multi-crops and a successful hotel on top. So how could I stop completely what I was doing for five full days to focus on a half-hectare plot? Turns out this was one of the best ideas I’ve had on my journey of better understanding the complexity around our food systems and the opportunities to change it.

Last Wednesday morning, instead of my usual marathon of Zoom calls, there I was with a massive compost bag over my shoulder, dumping it with care on the tree and vegetable lines we were about to plant. Be the Earth Foundation partnered with Green Hearted, a South African organization with two of the best teachers I’ve ever met in Syntropic Agroforestry: Kate Curtis, who had broad experience running workshops with Ernst Götsch in Spain before devoting her work to building systems in South Africa, and Alex Kruger, a veteran of building and teaching agroforestry systems with local South African species, including medicinal Cape Flora plants that I was keen to see applied in a syntropic agroforestry.

The class had an interesting mix of community leaders, local practitioners, and entrepreneurs—from people managing very limited land and resources in school backyards in townships around Cape Town, to those managing their own farms or community projects throughout the country. The common theme was building food security in their communities and the love for nature.

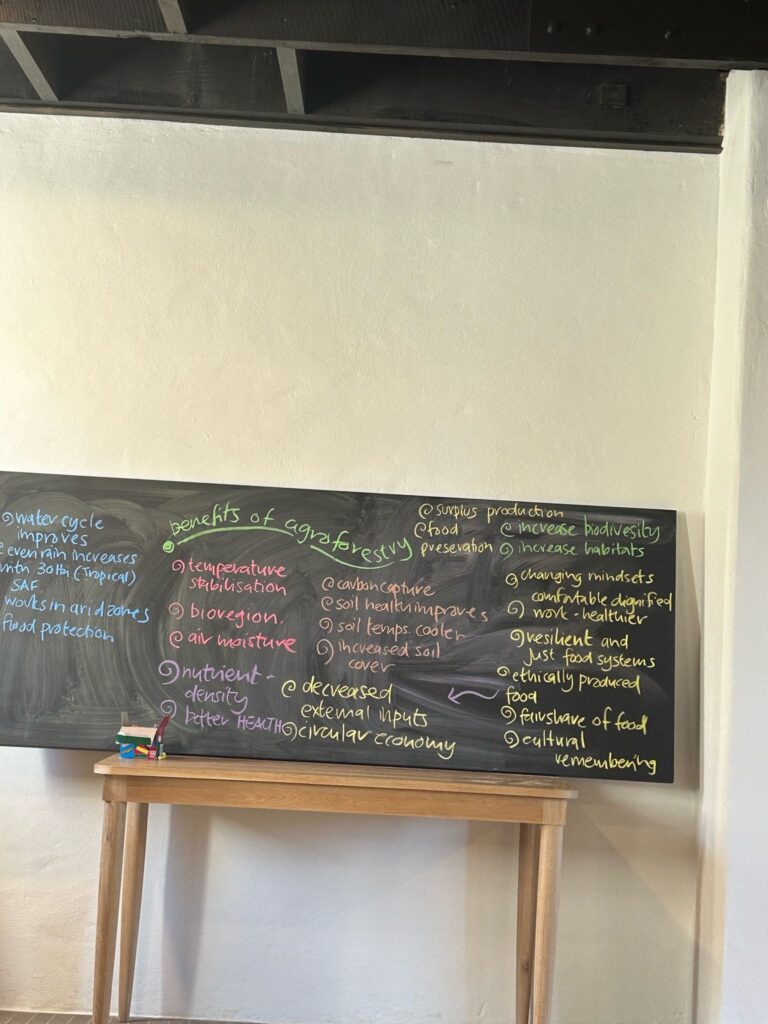

The beauty of the agroforestry system is how we can replicate the logic of a forest, where trees and shrubs in different layers work in succession to maximize photosynthesis with lots of interspecies collaboration, in a farm system that gives us production with diversity and resilience.

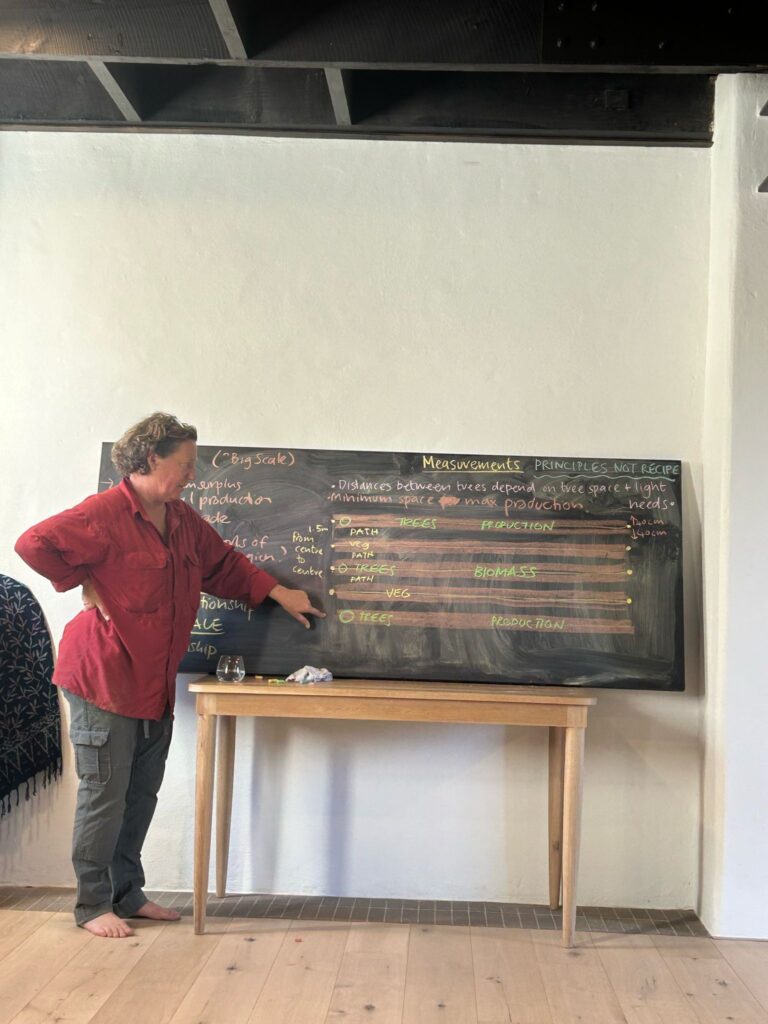

On the system we were planting over the next five days, we would plant lines of Mediterranean trees, with productive species such as citrus, figs, almonds and pecans adapted to the Cape climate, with lots of indigenous support species, and elaborate a timely succession plan where we would grow vegetables while the trees were still growing—farming as much as we could of the abundant Cape sun, while creating the proper ground cover to save us the precious water humidity for the system to thrive. With all the climate weirdness around us, we would also pilot lines of subtropical fruit species such as avocado, lychee, papaya, banana and custard apple to see how they would thrive with the support of many resilient locals and the creation of lots of biomass.

Besides learning all the technicalities of spacing between species and the best conditions to help nature support the system, planting it myself in community work opened a whole new perspective. Often, we business people—from entrepreneurs to corporate executives—love planning and applying the latest technology to agriculture, but never really get our hands dirty in soil.

The first discovery was quite illustrative of our disconnect. As my back hurt working with the small shovels used in agriculture here in South Africa, I discovered the local tools were originally built for small, cramped spaces in mining. They were just moved down to agriculture as they were, without any business people really bothering to look at the opportunity of more ergonomic farm tools until very recently. We are too busy building drones and robots in comfortable offices to look at mundane farm equipment. No wonder most of the technology for agriculture that gets created is stuff farmers don’t really need.

Then comes the pruning, propagation, and wild seed collection. Turns out a small farm like the one we were working in, with a few square meters of lines implemented, is already yielding enough seeds and biological material to kick-start 20 other farms like this. That’s why farm nurseries are so important.

The use of mostly indigenous support species means that as farmers develop their agroforestry systems, they become less and less reliant on buying seedlings and seeds. Add to that the fact that the system generates its own biomass, and what we have is the capacity of communities to build food security with input independence, making them much less vulnerable to market fluctuations.

The farming method of planning a system for succession also allows for alternative short-term crops, such as vegetables, to be grown while the high-yield trees are not mature yet. It’s a whole different farm game than the usual one of planting a monoculture and waiting for it to mature, holding debt and all the risk of something going wrong with your one crop—from pests and diseases, to climate events and market fluctuations. The syntropic agroforestry system embraces the complexity of diversity, encourages community work, and holds the possibility of farmers going back to the not-so-distant past when real food was grown on farms together with the cash crop, before industrial agriculture turned farming into a soul-crushing mechanical work of men fighting nature with chemicals, turning farm communities into food deserts.

There is good momentum for an agroecological disruption of our broken food system from the bottom up, and agroforestry is an incredible community tool. It thrives on diversity, resilience, human creativity, and collaboration with plants, fungi, bacteria and insects. It’s about communities claiming back their seeds, growing back native crops in whatever small space they have available—from backyards to farms. It’s us humans getting our hands in the soil again and reclaiming farming as an art, sharing seeds, agroforestry designs, and making the edible industrial crap business people taught us to call food as old-fashioned and rejected as cigarettes.